Tottori University’s adaptation measures for Japanese pear cultivation

| Date of interview | September 6, 2021 |

|---|---|

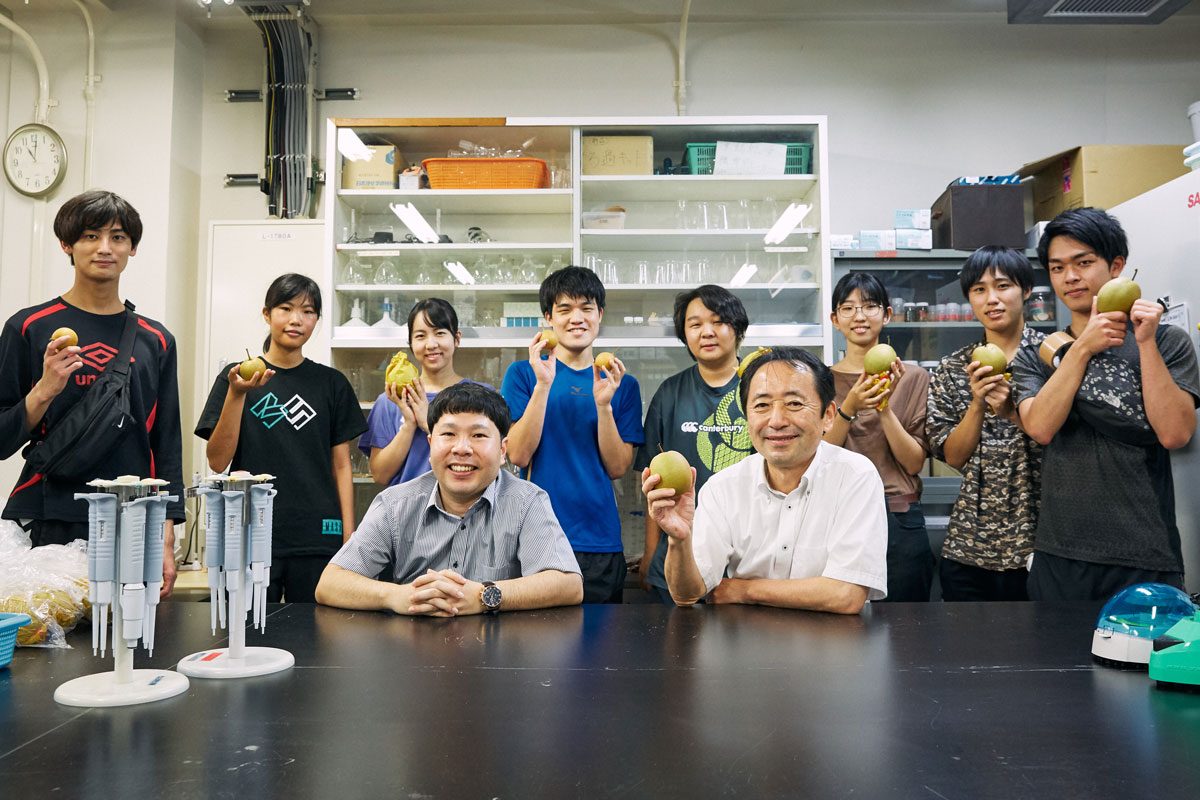

| Targets | Dr. Fumio Tamura, Trustee (Education and International Exchange) & Vice President, Tottori University (National University Corporation) Dr. Yoshihiro Takemura, Department of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, Tottori University (National University Corporation) |

Climate change impact

Please tell us about the research projects being conducted at the Laboratory of Horticultural Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Tottori University.

Dr. Takemura: Our Laboratory studies horticultural crops such as fruit trees, vegetables, and flowers. We have been focusing on fruits broadly – Japanese pears in particular – because they are significantly more affected by global warming than most other crops, with a view toward elucidating the mechanism through which abnormal blooms occur, etc.

About pear blossoms, please tell us when you came to realize they were being impacted by climate change and what you noticed at the time.

Dr. Tamura: Since we started studying them around 1990, we have been recording annual meteorological observation data. So it was toward the end of the 1990s that we started noticing something odd was occurring with the climatic and meteorological conditions. Although the impact on our pears was initially negligible, the oddness would become more pronounced and frequent in the early 2000s when winter came around, as I recall.

More specifically, here in Tottori Prefecture, snowfall occurs frequently, but I noticed more and more that the snow would melt away quickly. Another prominent phenomenon I remember is high temperatures during fall. Foliage abscission would occur progressively later in the year as the flowers would bloom earlier than normal. Then, all of a sudden, winter temperatures would drop at other times, and the tree branches would get damaged due to the cold, and so on.

Adaptation measure formulation

So given the effects of climate change you have just described, what were the first activities you initiated?

Dr. Tamura: Pear trees have a built-in mechanism due to which spring sprouting does not occur unless they accumulate a certain amount of cold inside them during winter. While this threshold of cold requirement varies from one cultivar to another, we started studying each pear cultivar to determine what its cold temperature requirement was in the initial period of our research.

Dr. Takemura: Deciduous fruit trees become dormant in winter in a manner similar to how certain animals hibernate. This is known as endodormancy. Once a plant goes into its endodormant state, it does not sprout even if the temperature is raised. Then the plant accumulates a necessary amount of cold during winter and blooms when spring arrives. However, as the winter temperatures have been getting warmer in recent years, making it difficult for those trees to accumulate enough cold inside them, we are witnessing increasing numbers of instances where they experience difficulty coming out of their dormant state in spring.

Dr. Tamura: To address the situation, we decided to employ a technique that would artificially disrupt their endodormancy. These plants have this special trait that allows them to come out of their endodormancy to a degree when exposed to stressors. So for example, if we give them a substance that disrupts their breathing patterns, or inject them with a plant hormone that regulates their growth, their dormancy gets partially disrupted.

We then learned that this technique could be used to compensate for lack of cold temperatures in winter, any excessive use of chemical substances is not desirable, so it would be important for us to breed new varieties that would require lesser amounts of cold in winter in our future research. Pear varieties such as akizuki, hōsui, and shinkansen are known to require lesser amounts of cold temperature that way. For additional cultivar development, our breeding project started as far back as 20 years ago, and Dr. Takemura is now studying the second and third generations of those cultivars.

Please tell us more about your breeding project.

Dr. Tamura: It is predicted that growing any existing varieties in any region would become difficult in the future as climate change progresses. So to address this, we are developing new cultivars that would require even less amounts of cold during winter.

For this breeding project, we studied over 100 varieties of Japanese pears in the hope of discovering ones that had far less cold requirements, but we could find none unfortunately. But we pressed on with our search and stumbled upon this natural pear variety native to Taiwan, which required remarkably low amounts of cold. This was 20 years ago.

Dr. Takemura: While those Taiwanese pears require significantly low amounts of cold, their taste is not so good compared to Japanese pears. So we have been breeding them to achieve the level of deliciousness similar to Japanese pears as much as possible. We have bred them three times already and are currently growing a cultivar that would meet our final goal.

This latest cultivar is a result of breeding them twice with Japanese pears, and the entire process has taken us roughly 20 years. It takes about five years from the initial planting to blooming, and then we harvest and eat their fruits, compare between different varieties to pick out delicious ones, and repeat the breeding cycle all over until the desired traits are achieved, which is extremely time-consuming. So in order to work around this, we also started developing DNA markers that would allow us to accelerate the variety selection process simultaneously with the breeding of cultivars. It is our hope that this DNA marker project would help us identify desirable cultivars in shorter periods and improve the overall efficiency of the breeding process.

Another adaptation measure might be to identify optimal cultivation sites. Please tell us what the status of your current research is on this.

Dr. Takemura: We have been taking to the field the cultivars that have been developed that only require low amounts of cold to determine which regions of Japan would be most conducive to their cold accumulation process. For example, sites at high elevations would allow the cultivars to accumulate cold inside them during winter compared to flat expanses of land. So we are contemplating a new research model that involves creation of maps to visually indicate which geographic areas would be suitable for the pear cultivation and how they would change over time, so that it can aid the process of selecting the varieties that would be optimally adaptive to each region.

You just explained to us how pears would get damaged by abnormally low temperatures as well as global warming resulting from climate change. Please tell us more about it, including how cold-induced damage might be related to poor fruit growth.

Dr. Tamura: Plants gradually get accustomed to colder temperatures. This process is known as cold acclimation, but it does not function well if the temperature range in early fall stays too high. As humans catch a cold when the temperature drops quickly, plants’ cold acclimation function becomes impaired and they would perish in the worst of cases.

In addition, it used to be the case that pear farmers would prefer it if their trees bloomed early, because it meant early harvesting and higher unit prices of their pears. However, if they bloom too early now, the risk of exposure to abrupt cold waves increases proportionally. As pear pollens do not properly germinate if the temperature falls below 15°C, they would not grow fruits normally even if artificial pollination is performed scrupulously in early spring. Furthermore, if frost formation or snowfall occurs, it could freeze their flowers to death. To avoid this, pear farmers occasionally make bonfires in the fields or operate frost fans to prevent frost formation.

Future outlook

Please tell us about any particular difficulty you may be experiencing in your work as well as your source of motivation related to research activities.

Dr. Takemura: As far as pears are concerned, we started the research not knowing the mechanism of endodormancy. So the biggest obstacle is that we have no option but to develop technology solely relying upon our own experience. And even if the mechanism is deciphered, it would take at least five years from that point to develop adaptive cultivars, plant seeds, and assess results, so we must be patient in all scenarios. So it goes without saying that our students helping with the research are only able to see the results of their work after graduating the university.

With that said, it still gives me a lot of pleasure to see any previously unknown facts get discovered by our research. However, even when new knowledge is discovered, we test its validity often suspecting that it might not be true. So our research is analogous to a non-stop emotional rollercoaster ride but that is part of the motivation to do my research.

Also, it gives me such a great pleasure when a new cultivar is successfully developed. I am the happiest person when I get to eat the fruit of a new cultivar for the first time and find out how delicious it has turned out, sharing the joy with my students.

Dr. Tamura: My former instructor once told me that I should not care who made key findings in a research project as long as they were found. So the bottom line is, as long as new knowledge is discovered by researchers, not matter who they may be, and the knowledge is eventually applied for the public good, that should be enough. Us researchers, we derive much fun and pleasure from the process of scientific research, so that’s my motivation. What drives me to live my life every day even.

Dr. Tamura: As global warming escalates, I think it would be quite difficult to sustain pear farming only with the existing varieties. According to some projections, pear cultivation especially in Kyushu and the rest of Southwestern Japan where the climate is temperate would become fairly difficult. So I am hoping that the pear cultivars we have been breeding would be grown in many parts of Japan, and their offspring would lead to even more advanced breeding activities nationwide, which might help sustain the current level of pear production in the future.

Dr. Tamura:Japanese pears have been essential fruits in the local culture since the Nara period. Therefore, it is quite sad for me to see that the existing varieties are on the verge of becoming unable to adapt to the environment. As those pears are a highly important part of our fruit harvest in fall and by extension our culture, I hope there is a way to pass them on to our future generations. As we are building knowledge and making breakthroughs on the identification of geographic areas that might be suitable for pear cultivation and on the creation of the cultivars possessing desired traits, I am hopeful that this research would eventually allow us to keep alive our tradition of Japanese pear cultivation somehow.

(Video posted on June 3, 2022 / Article posted on December 9, 2021)