Climate Change Adaptation Measures in Agriculture of Hokkaido

| Date of interview | September 16, 2020 |

|---|---|

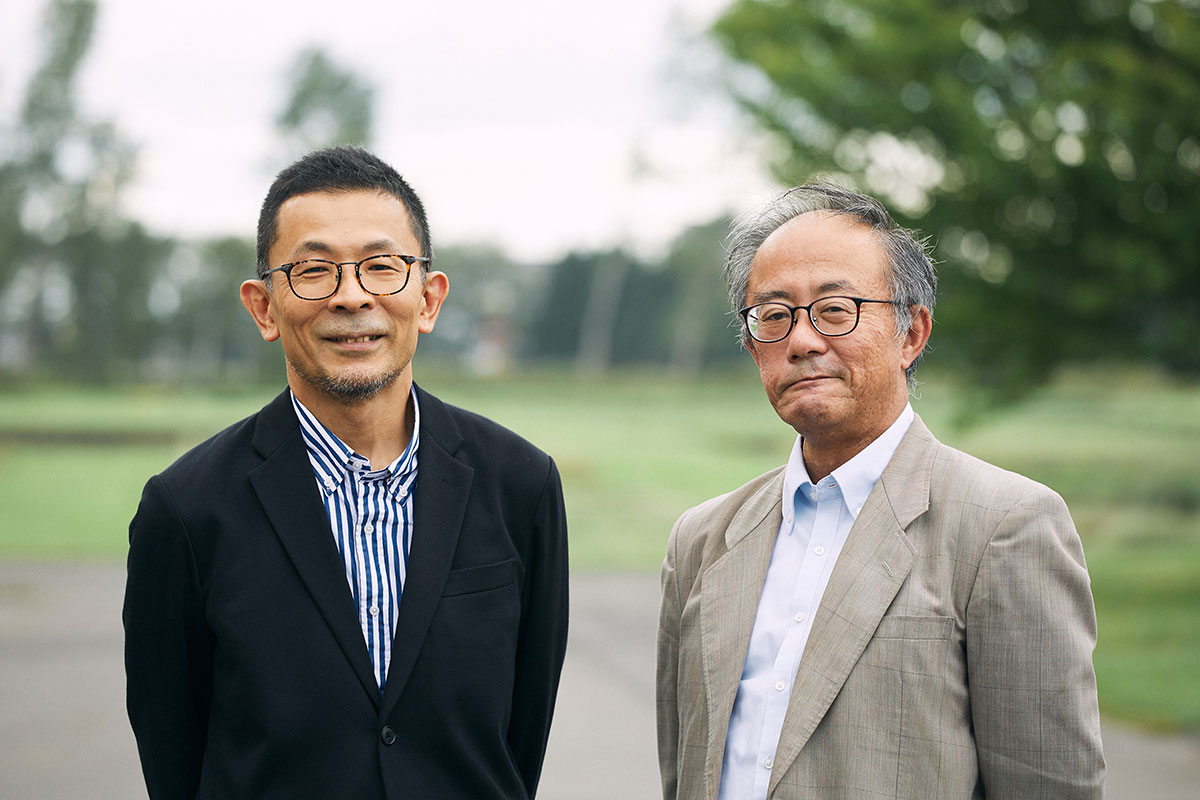

| Targets | Hokkaido Agricultural Research Center, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization Yasuhiro Kominami, Group Leader, Meteorological Information Group, Division of Farming System Research Satoshi Inoue, Senior Researcher, Climate Change Group, Division of Agro-environmental Research Tomoyoshi Hirota, Professor, Department of Agro-environmental Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University |

Please describe to us the outline of the organization and details about the efforts at the Climate Change Group, Hokkaido Agricultural Research Center, National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO).

Mr. Kominami: We study various crops grown in Hokkaido using agricultural meteorology, which examines the relationship between crop growth and weather environment. At present, we have 4 researchers. We mainly deal with climate change, and work on the construction of information systems to share the changes in agriculture caused by climate change with the producers, introduction of new crops, etc. I was appointed to my current post in April this year, and Professor Hirota from Kyushu University had been working as the group leader until March. I asked Professor Hirota to participate in the interview online.

Please tell us about the timing at which you started grasping the impacts of climate change in agriculture of Hokkaido, and the background for working on the research.

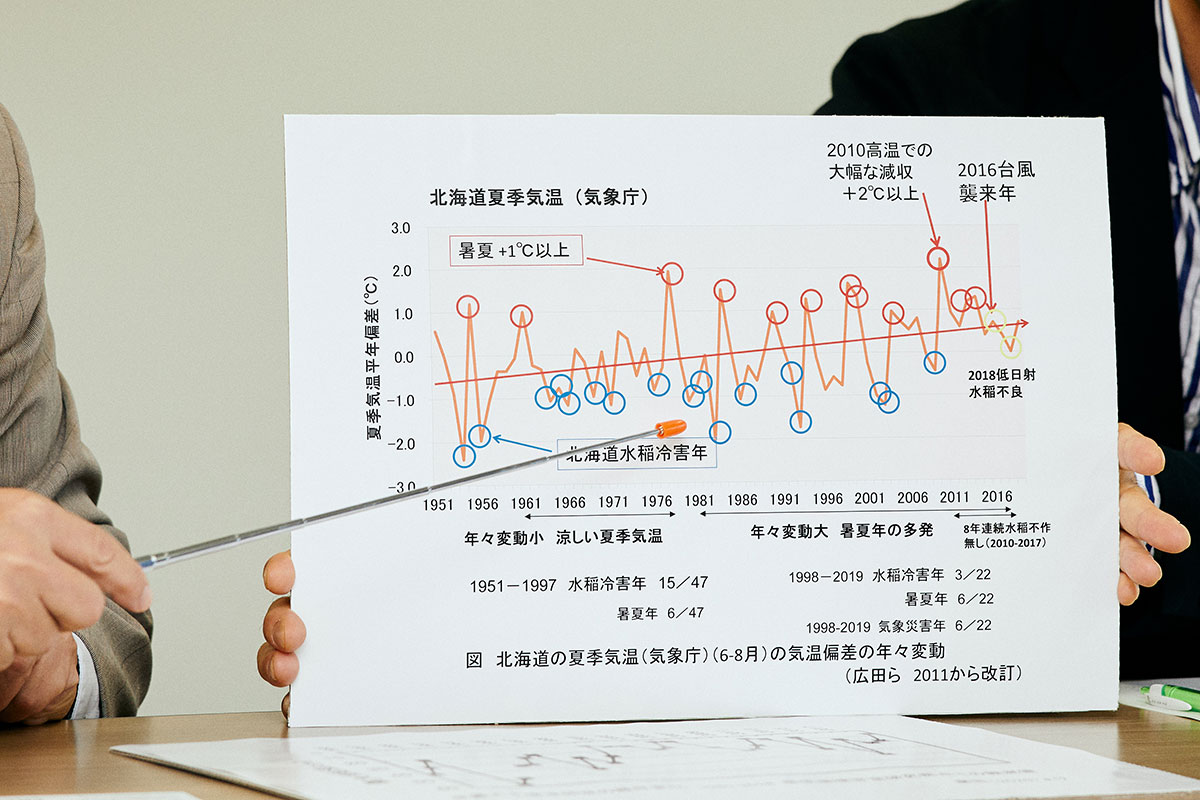

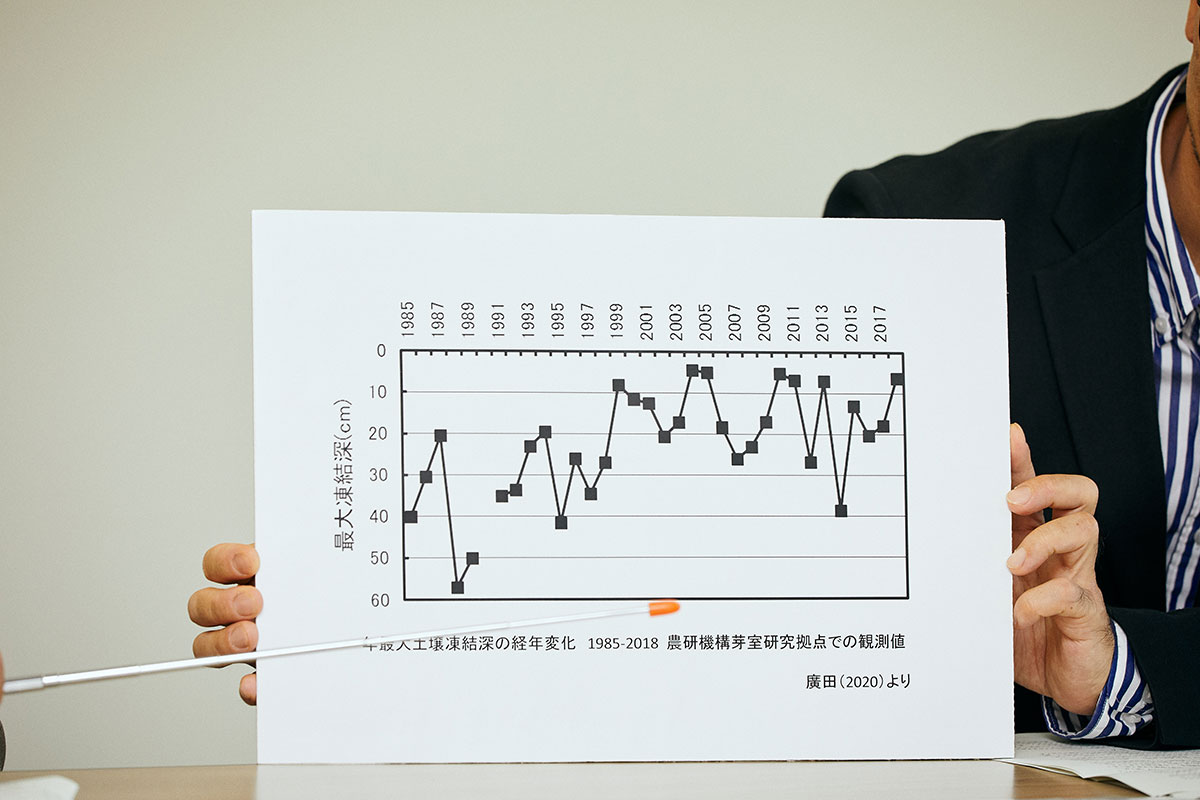

Mr. Kominami: I heard that Professor Hirota observed a decreasing trend when he studied the soil freezing depth in the Tokachi and Okhotsk regions during winter after he learned about studies on soil temperature fluctuations and soil freezing when he stayed at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada for 1 year and a half since 1999. In addition, phenomena that can be considered abnormal weather seemed to increase after the great cold summer damages in rice in 1993 and the intense heat in the summer of 1994.

It was after the turn of the century into the 21st when we started research from the viewpoint of global warming and climate change. Research focused on climate change as the target began in 2006, which established the Climate and Land Use Change Research Team. I have been involved in this case in an additional post since when I was posted at a branch of the Central Region Agricultural Research Center, NARO in Niigata Prefecture. This team had a system for researchers of mitigation measures who studied the greenhouse gases from agricultural lands and researchers of adaptation measures in agricultural meteorology to cooperate in conducting research, which accelerated the research on climate change.

What effects did you observe in the field due to the decrease in soil freezing depth?

Mr. Hirota: The Tokachi and Okhotsk regions have cold winters where the temperature often reaches -20 to -30C with little snow accumulation, and therefore have been known as regions where the ground froze. However, the soil freezing depth began to show a tendency to decrease over a long period, as snow, which has thermal insulation effect (while snow consists of small grains of ice, it also contains a lot of air and becomes a thermal insulation material when it accumulates by 20 cm or more), accumulated early in the winter. It was the issue of volunteer potatoes that the decrease in soil freezing depth caused a large impact.

Although small potatoes that are left in the soil after harvesting with machines had withered and died due to the soil freezing before, they began to pass the winter and grow wild in the second crop field as the soil freezing depth decreased. These small potatoes are called “volunteer potatoes.” Volunteer potatoes need to be controlled, as they not only compete with the growth of the crop that is to be planted after potatoes but also act as sources of diseases and pests. The producers therefore have to pull out the volunteer potatoes manually or spray agricultural chemicals, which resulted in labor of a few dozen hours per worker per hectare. This was an unexpected increase in labor burden. Decrease in the soil freezing depth also allowed the meltwater to permeate into the soil earlier. While this was a good thing in that the soil in the fields could be dried earlier and the farming work in the spring could be started earlier, it caused the nitrogen in soil to dissolve in water and run deep into the ground as a consequence. It led to the concern for increased environmental load including groundwater contamination, in addition to the decreased nitrogen utilization efficiency by crops.

Meanwhile, there are also case examples of favorable impacts of climate change. In pasture grass production, it became possible for alfalfa, which is susceptible to freezing and had been difficult to cultivate especially in eastern Hokkaido, to pass the winter, and it expanded the cultivation area. It also became possible to have Chinese yam, which is a well-known export crop from the Tokachi region, pass the winter and harvest in spring, though it had been mainly harvested in fall, allowing distribution of labor, work, and shipment compared to before when work had to be concentrated in the fall. I consider this a favorable impact of climate change, as this became possible due to the decrease in soil freezing depth.

Mr. Inoue: Some also say that the taste of rice improved due to breed improvement and warming, although the taste of rice harvested in Hokkaido had not been so good before.

Please tell us about the efforts that are already implemented as measures against climate change in agriculture of Hokkaido.

Mr. Hirota: To handle the problems in agriculture that occur due to the decrease in soil freezing depth, we developed a method to control the soil freezing depth taking the opportunity of volunteer potato measures. Specifically, we first calculate the soil freezing depth based on the weather data, facilitate freezing by conducting snow removal and compaction, and control the soil freezing depth to the optimal value. We elucidated that the freezing depth that can control the volunteer potatoes was 30 cm. In this method, we return the removed snow or leave the snow that has fallen afterwards unattended once the freezing depth reaches 30 cm using this result, and prevent the soil from freezing farther.

We put this control on soil freezing depth into practical use as a system on which the producer can develop their own work plan on the web. They can plan to maintain the appropriate soil freezing depth by conducting snow removal or compaction at certain timing. This method achieved dramatic labor saving and chemical-free control, as the manual work that had required considerable time in the busy summer before can now be conducted by machines during the winter when they have the time. As it became possible to control the soil freezing depth, we can also expect the effects to prevent the nitrogen in soil from leaching and prevent the emission of greenhouse gases, in addition to volunteer potato control. It has expanded into a technique which improves the pulverization property and draining property as the soil freezes while maintaining nitrogen, which results in increased productivity and yield.

Mr. Inoue: I conduct research on pasture grass. The nutritional value and digestibility deteriorate, and the amount of milk from the cattle is also affected when there are more weeds on the pasture. The producers therefore sowed the seeds of pasture grass that have high nutritional value in the spring, and purchased pasture grass by the amount that could not be harvested on the land. However, climate change accelerated the growth of pasture grass in recent years, allowing the pasture grass to grow high enough to pass the winter before winter came, even when seeds are sowed during the summer after harvesting the first crop, and contributing to saving of feed cost. Our group has developed a program to calculate the timing of seed sowing based on the Agro-Meteorological Grid Square Data of NARO so that the producers can sow the seeds at appropriate timings. It calculates and transmits the daily weather data including forecasts in 1 km grids. We are also operating many systems, including snow breaking and removing, snow compaction, support for wine grape cultivation, cultivation and management support system for paddy rice and wheat, etc., using the Agro-Meteorological Grid Square Data.

The Hokkaido Agricultural Research Center has also established a portal site to provide links to such information that utilize the Agro-Meteorological Grid Square Data, and transmit information for easy use by the producers and concerned parties in agriculture. However, we face some difficulties in continuing the operation as to whether the developed systems would pay economically or not. As future developments, we hope to make improvements so that they are more precise and advanced, and make available to the public new techniques and systems as we are also conducting research on other items.

Have you made any creative efforts in providing information, and is there anything you are already working on?

Mr. Kominami: Since it is extremely important to present the information in an easily understood manner, we placed importance on making it easy to understand by asking Agricultural Cooperative and other parties to which we provide the data to collect information on the demands by conducting questionnaires to union members, etc.

Mr. Hirota: To supplement a little on the comments by Mr. Kominami, it is important to create by working with the people in the field instead of researchers creating the systems unilaterally in development of information systems to be used in the field of agriculture. Although such a style requires trial and error and a long period of development, it will be a practical system with which both parties are satisfied by listening to the voices from the field. We developed a system for soil freezing depth control that can deliver the information directly to the field by using the data and uploading it to the information system.

Mr. Inoue: Hokkaido has an organization with dissemination workers to transmit the information to the producers in the field called the Agricultural Technologies and Extension Division of the Department of Agriculture, and they developed a manual for “what instructions should be given with which focus this month.” Since they introduce the calculation method for pasture grass seed sowing that was mentioned earlier, etc., the dissemination workers utilize these tools when giving instructions to the producers.

Finally, what gives you the sense of satisfaction in working on climate change and adaptation as a national research institute?

Mr. Hirota: What I felt while I was assigned at the Hokkaido Agricultural Research Center was the advantage to be able to start from basic research because it is a national research institute. I have experienced various things regarding climate change adaptation, from basics to application, technological development, and dissemination. We implemented dissemination while considering the method to promote effectively with every possible creative means. While research and technological development often completes once the purpose has been achieved, and we start from zero again in the next item, we are able to connect one success to another success as we started from basic research and developed from there. A good example of this is the soil freezing depth control method being expanded from volunteer potato measures to methods for improving productivity and reducing environmental loads. This is an important message from me in expanding the successful case examples of adaptation measures.

Mr. Kominami: When we conduct farming in large fields that we see in Hokkaido, the density is low since the profit per area is small. Since it is difficult to spend money on hardware including infrastructure, it is necessary that we make the best of information systems. As smartphones and tablets have become popular among producers as tools to receive information today, I hope to contribute to the agriculture of Hokkaido by putting the weather data, global warming future prediction data, etc. to good use.

Mr. Inoue: While the food self-sufficiency ratio in Japan is lower than 40%, it is 200% when we only see Hokkaido. It is an area which produces nearly half of Japan’s national production in raw milk production volume alone. Since there is land, they can conduct dairy farming while growing pasture grass. This is why 70% of pasture lands in Japan are in Hokkaido. Hokkaido has several dry field crops which they produce in highest yield among all the prefectures, and rice has improved in taste until it is nearly equivalent to those produced in Honshu. While we were studying the local climate change in Hokkaido, our results actually have large national impacts. That I can conduct research in such a characteristic place gives me a great sense of satisfaction. It is our mission to think about how safe we can make the crops that everyone eats, and how inexpensively and stably they can be produced in Hokkaido. Since we still have the method to try the agricultural techniques from Honshu in cooler Hokkaido regarding climate change, I believe that we have plenty of possibilities to positively adapt.

(Date of publication: December 7, 2020)